As I am working on my next campaign, I thought I would take a few minutes to write some of the context that goes into that. For this post we will have two parts: 1) elements of play and 2) trade-off between combat systems.

Element of play or What the heck is this game going to actually be?

The early Blackmoor campaign, from which D&D was derived, was an odd mix of mostly crawling a single large mega dungeon with characters being units from a war game, raising an army for the big end battle, and then a smaller mix of one-off adventures in the land. 1st and 2nd editions of D&D, or OSR if you prefer, are also focused on a mix of smaller dungeons and hex crawling. In the early game, getting a burst of power to work through a dungeon works. For a mega dungeon… not so much. Raising an army for large battles was important in Early D&D but only in late game. Modern D&D is mostly split between DM’s doing small dungeons with a specific theme and then lots and lots of characters and one-off adventures matching them.

The reason why this matters is because we have to call out what a character needs to do if we are making something like a class or character creation process. Given the previous ideas:

While every campaign is different, between the editions there has been a shift in focus on what D&D games are and are not. On what kind of content they do and do not tackle. One of the reasons why more recent versions of D&D have struggled with designing Fighters is because in the early version the two most important things about Fighters is their ability to raise armies and their use of magic swords. Now everyone gets magic items and they are not raising armies, i.e. everyone is now part-fighter and half of the Fighters job is no longer a core part of the game. No wonder they are bland.

There is also this core idea of player feedback in response to the content. Originally there was no thief class. Players created the thief class and suggested it to TSR, not TSR offering it to the player. And the original thief class is a completely logical response to a dungeon filled with traps and trickery. As the published modules started to lean on hex crawls more and more, the Ranger class went from a specialty within the fighter to its own stand alone thing. The Ranger class and its themes only really make sense in a game that is leaning into that niche of content. Rangers in 5e struggle… because they are best Hex Crawlers in a game that does not hex crawl.

So if you ask me “How do I make a good Ranger class?” my answer to that will vary wildly based on which edition of the game you are playing or what kind of campaign you are running. In a Dark Sun like setting where you have to scavenge for water, Rangers are totally overpowered. In a generic superheroes in high-fantasy setting, Rangers have lackluster DPS.

So in this next campaign, what are the marquee ideas I am pinning the campaign on?

- Mega-Dungeons… or at least much larger dungeons with interactive elements between sections.

- Hunting down great beasts… with a focus on turning their hides into armor and weapons

- Faction Play… with a focus on building an army, raising a castle, and improving the realm with infrastructure

- A Real Time game, so one day in the real world is one day in the game. Time is a resource you use for self healing, regaining magic, crafting, self training, and training others.

So how do these ideas affect the game? The biggest is how the real time game interacts with magic. There is always a cost to regaining magic so there is always an incentive to not cast a spell. At the same time, there is a meta level of play where magic users can stack up a large pool of spells in their magical arsenal. It is best to look at magic users not in terms of long rest but instead in terms of their total magic over their career.

Tools, which are throwaway items in 5e, are actually super critical to helping you and your allies to power up. Crafting will be more powerful and reliable than enchantment magic. It also means that many players will be dependent on other players for their “level up”. I double down on this idea with a team being needed to hunt down large monsters to make better weapons and armor but that creature only giving a limited amount of crafting material.

And finally, given the faction play element, it is important to look beyond your character and instead look at your role in the world. Gaining +1 soldiers is more powerful than gaining +1 to your sword hand when fighting in a big battle. This creates a very different leveling experience because you are facing a trade off between different elements of play.

This goes back to the classic failure of modern D&D players to read only the class section of the older player handbooks and declare that Fighters are linear. They are not, they keep gaining extra attacks and more health via adding more minions to the battlefield. Neither the Beastmasters Ranger nor conjuring Wizards are the best pet class in D&D. The 1st Edition Fighting-Man is the best pet class in D&D. That is why Fighters use basic mechanics. You’re basic because you will be playing 4 Fighters at once.

Of these three examples, note how they interact with each other. Crafting, regaining magic, training others, and resting to recover from tanking a dungeon all share the same resource: Time. Something like an Eldridge Knight or a Bladesinger becomes challenging in this system because they would want to drop all their Time into resting and regaining magic, but doing that ;eaves them with nothing left for Faction Play or leveling up their character with training and crafting. Those kinds of apex dungeon crawlers can be a thing… just know that sustaining those is hard and comes at a cost to other parts of the game.

The Iron Triangle of Combat Systems

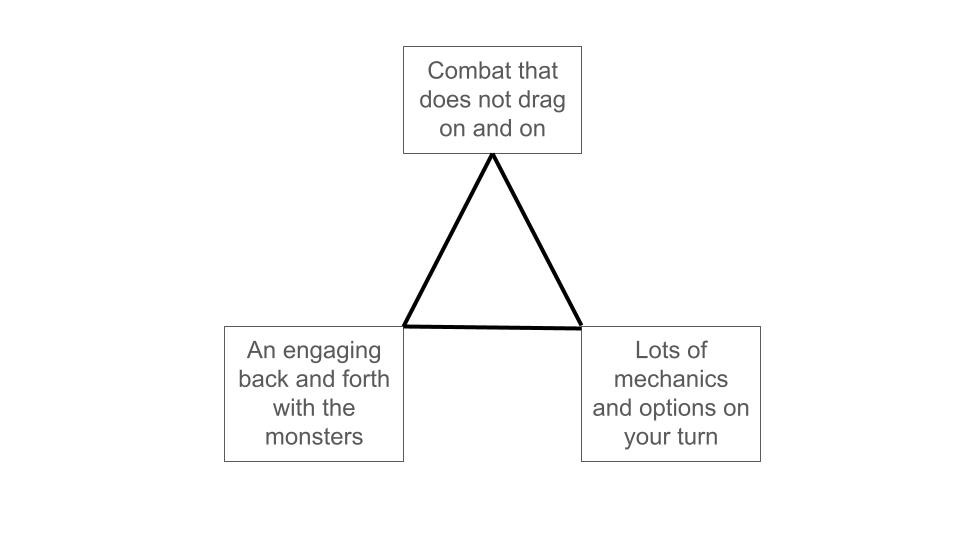

This is the iron triangle of tabletop RPG systems. You can pick any two options for your RPG, but you can never get all three.

Now all of these three ideas are good insights and fun ideas. There are plenty of reasons to support any of these and any combination of these. However, as a designer I have to accept that I will always sacrifice the third option is I prioritize the other two.

For 5e D&D, the vast majority of combat ends in 2-3 rounds. That is the game working as intended. But as a DM and storyteller, I hated this. It removes any chance for the party to have to regroup and find a new approach to re-engage the enemy. That engaging back and forth matters. I find this hilarious because this is actually something the D&D movie gets right but that game gets wrong. From the first few scenes of the movie you know that Chris Pine’s bard is going to have to outwit the final boss. And he does in an entertaining way. But it is only entertaining because one the first attempt it failed. More rounds were needed for the regroup and second try. That is just the basics of good storytelling.

The problem is if you want those fights with lots of player options and power as well as the back and forth, that is just a really long fight. Great for the climax of a film, too many hours at the table. This is part of the mistake 4th edition D&D made. Combat took way too long and was way too complex. 5e was largely built on 4e’s math and 3.5e character sheets but with things gutted down to a 2e level of simplicity, or at least as close to that level of simplicity as they could get. The key with 5e being that they designed the characters and monsters to be 2-3 fights because they were actively avoiding longer fights.

And that is the choice here: 1) the 5e approach of lots per round but only 2-3 rounds or 2) what I just did in Star Chaser with 6-10 rounds but less options per round. Both systems preserve the top of the triangle. I think that part of the Triangle is the most mandatory just due to the practicality of running games regularly.

Now in Star Chaser I did sneak around that a bit. Most sessions were the red line while one or twice a year we had a series of green line sessions. Those green line options were large scope battles that lasted multiple sessions. I did this not by giving each character more options, but instead just gave everyone many simple characters to play all at once. I think that worked well in the campaign, fits right in with what the Blackmoor campaign did, and is actually what the D&D movie did as well. I think this mostly red line to sometimes green line but never blue line design is what the OSR community has backed into. The problem being that as time goes on, the obvious addition is adding in more things to classes which pushes you from the red line to either the blue line (with weaker monsters) or the green line (with stronger monsters).

Combining these two frameworks

Traditionally a character class is define as “here is the list of cool powers you get”

So what is a character class in a system with a focus on:

- Faction level play

- Combat with lots of rounds but minimal per round

- A focus on very large dungeons with real resource limitations

- And character growth limitation governed by Time, not selecting between bonuses

That is the challenge I am working through. This is not about balancing the DPS of different classes. This is about larger structural questions on how a class would interact in a much larger world and seeking more long term goals.

And that says nothing of things like characters aging, creating a lineage of characters, or the details of Kingdom management and technological development or magical development. This is not really a class system but a whole series of class system applied to different aspects of the game.