For this post we are going to analyze just 6 measures from single song to figure out how we can write better basslines. The song is Ain’t No Mountain High Enough by Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell. It is a Motown recording using their studio band, the Funk Brothers, with James Jamerson on bass. James Jamerson is one of the most influential bass players of all time so if you are unfamiliar with him, go do your homework and then come back.

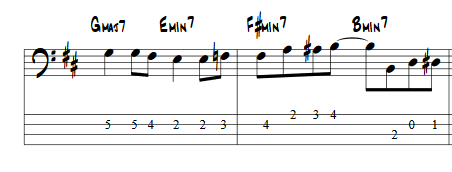

Listen to the song if you don’t already know it. This version has the bass turned up and has a visual for the bassline. The sheet music below is from www.thebassment.info.

So this is just 75% of the chorus and you have a fairly a straight forward 4 chord progression.

G… E… F#… B…

If you are used to 4 chord power songs then you already know a dozen different fills to connect these chords. This is slightly different as it is in the key of Bm with you ending on the root. Thus you have a traditional 6 – 4 – 5 – 1 line. Otherwise, nothing really note worthy here, and most bass players would have played some simple licks to connect the parts and moved on.

But not Jamerson… and lines like this are why he is a legend.

Take just a second to think of a more traditional bassline under this song using some of the riffs you already have in your arsenal. You make it sound a bit funky, you put a bit of groove in it, and I’m sure you execute on it well. Listen back to it in your head I sure it sounds good. But does it have that rolling roar of a Jamerson line? So let’s break it down.

Using Octaves Asymmetrically

So we have our line of 6 – 4 – 5 – 1 in the key of Bm, but what octave do we play it on? For many the answer is often either what has the tone we want or if we specifically want to play the root higher or lower then the rest. On lines that end on the root, we often play it lower than everything else to give it extra oomph and create a feeling of resolve with in the line.

So what does Jamerson do with the root notes of the chords in terms of octaves?

Low – Low – Low – Low

High – High – High – Low

High – High – High – High

Each line is different. We start low, go to a mix, and end high. That is 3 different basslines just in terms of the where we place our root notes. Let’s look at the transitions between roots.

Low (go up to walk down) Low (walk up) Low (walk up) Low (walk up)

High (bounce around) High (walk up) High (go down to walk up) Low (walk up)

High (walk down) High (walk up) High (walk up) High (go down to walk up)

Every transition is different from line to line with one exception. The transition from Em7 to F#m7. This one part is the same every time. Notice he also walks up 7 of the 12 times, walks down 3 times, and bounces around only once. This is mostly an ascending line with intentional movement to make dramatic moves down so he can chromatically walk back up.

Using Rhythm Asymmetrically

Jamerson is a bit less dramatic here (not so with the verses, but that is for another time). The first and third pass through the chord progression we see the same rhythm. Note that by holding out on the & of 2 in the second (and sixth) measure it breaks the 1 and 3 flow from the first (and fifth) measure.

1 – 2 & 3 – 4 & | 1 & 2 & – & 4 & |

1 & 2 & 3 – 4 & | 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & |

1 – 2 & 3 – 4 & | 1 & 2 & – & 4 & |

The second line reflects the first and third pass through the chords, in fact is one note busier in each measure, which is every other chord. This means it still feels very close… but isn’t quite the same.

Bring the Asymmetrical Element Together

So what is the big picture of these 6 measures?

Low Octave – Rhythm 1

High/Low Octave Mix – Rhythm 1 with slight variations

High Octave – Rhythm 1

He uses similar chromatic walk up throughout. He keeps the relationship between the Em7 and F#m7 the same at all stages. He never radically changes the style or tonality. That said, go listen to the song again. That chorus has a this rolling roar that brings you in and is constantly shifting below your feet.

In an earlier blog post I ranted against musician’s obsession with tone, and I concluded with the idea that if you feel like your tone is lacking, maybe the problem is with the bassline you are playing. In an earlier post I also talked about the role of a bass player as selecting between great lines, not just being good enough to play one good line. The exercises needed to seek out those better basslines are the same kinds of approaches that can be applied across a verse or chorus to create a dynamic asymmetric bassline. Notice that we are ignoring our preferred tone across octaves to write a line that moves across octaves.

And that is part of the barrier to asymmetric basslines. You must put the technician aside and lean hard, hard, into the musician side for being a bass player. A bias for specific tones or specific riffs will actually stand in your way as you try to write broader lines.